Chiltons Rabbi Jesus auf Deutsch - eine triumphale menschliche Tragödie

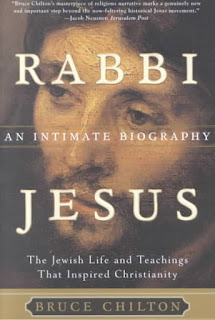

Bruce Chilton: Rabbi Jesus

Historisch-psychologische

Rekonstruktion einer Tragödie

|

| Bruce Chilton: Rabbi Jesus deutsch |

Ein durch und durch menschliches Schicksal, das die Welt veränderte

Bruce Chiltons Buch "Rabbi Jesus" ist die überaus spannende Geschichte über ein durch und durch menschliches Schicksal, das vor 2000 Jahren im antiken Galiläa stattfand. Präzise beschreibt Chilton die politischen, sozialen und kulturellen (jüdischen) Bedingungen, unter denen Jesus aufwuchs. Stets um solide wissenschaftliche Fundierung bemüht konstruiert Chilton aufregende und bestechend plausible Hypothesen über die psychologische und spirituelle Entwicklung von Jesus. Chilton versucht sich von konventionellen Lehrmeinungen zu befreien und Jesus aus seiner damaligen Vorstellungs- und Begriffswelt heraus zu verstehen (so wie ich als Psychotherapeut versuche, Patienten nicht (nur) in theoriegeleitete Schubladen einzuordnen, sondern - so gut ich kann - sie aus ihrer ureigenen Innenperspektive zu verstehen). In erfrischender Weise widerspricht Chiltons alternatives Jesusbild bekannten theologischen Konzepten.Chiltons Jesus leidet an den gleichen Zweifeln und Sorgen und kämpft mit ähnlichen Problemen wie andere Menschen auch: "Die Stärke von Jesus gründet in seiner Verletzlichkeit (...), die ihn durch sein Leben hindurch auszeichnet. Er lädt jeden von uns ein, ihm in jenen gefährlichen Bereichen zu begegnen, in denen das Gewahrwerden unserer eigenen Schwäche und Zerbrechlichkeit das Selbst zerschmettert und ein Bild von Gott in uns erblühen lässt." Chilton bringt den Leser in Berührung mit dem "inneren Menschen" Jesus. Er geht dabei nicht selten über das hinaus, was aus den Schriften belegbar ist. Und Chilton macht stets deutlich, dass die Geschichte von Jesus auch in ganz anderer Weise rekonstruiert werden könnte.

Die facettenreiche Biografie von Jesus endet in einem tragischen, aber triumphalen persönlichen Scheitern. Denn Jesus war es nicht vergönnt, sein eigentliches leidenschaftliches Anliegen, die Reformation des Tempelkultus in Jerusalem, zu verwirklichen. Chilton wörtlich: "Der Tempel, den er (wie die meisten anderen Juden seiner Zeit) so sehr verehrte, wurde ebenso zerstört wie sein eigener Körper. Er hinterließ im Judentum keine dauerhaften Spuren. Er war bereits im Alter von 30 tot und hatte noch keine eigene 'mishnah' (eine ausgeformte öffentliche Lehre, die ein Rabbi mit rund 40 typischerweise seinen Schülern übertrug) geschaffen." Aber das finale Disaster an einem römischen Kreuz erwies sich schließlich als der Startschuss der gewaltigen Erfolgsgeschichte des Christentums, etwas was Jesus wahrscheinlich niemals beabsichtigte.

Ein großes Ziel, das es noch zu errreichen gilt

Für Chilton hat sich die Theologie viel zu stark darauf konzentriert, "Jesus zu erhöhen als den einzigen Menschen, der zur Rechten Gottes sitzt". Viele Theologen hätten "anderen den Himmel verweigert", weil sie die "entscheidende Wahrheit" unbeachtet ließen, welche Vision Jesus tatsächlich lehrte und wie er sie verwirklichen wollte.Für Chilton gibt es noch ein großes Ziel zu erreichen: Die Vision von Jesus mit der gesamten Menschheit zu teilen. Der Rabbi von Nazareth hat nie behauptet, er sei einzigartig. Sein Abba (das aramäische Wort für Vater) war der Abba aller. Jesus formulierte nie eine Doktrin oder konfessionelle Regeln. Es waren vielmehr die Ereignisse in seinem Leben und sein öffentliches Lehren, aus denen die besonderen emotional wirksamen Rituale wie Taufe, Gebet oder das Abendmal hervorgingen. Seine Visionen behielten ihre transformierende Kraft durch jene, die hofften, dass sie Gott durch die Reinheit ihres Herzens sehen und begegnen würden.

Meine eigene Sicht

Ich habe das Buch von Chilton aus meiner Perspektive als Arzt und Psychotherapeut gelesen. Als Arzt will ich menschliches Leiden, Angst und Verzweiflung lindern, einschließlich meiner eigenen. Positiv gesprochen möchte ich Menschen dabei unterstützen, sich besser, befähigter und ermutigt zu fühlen. Ich möchte ihr Vertrauen in sich selbst und in das Leben stärken. Ich habe ein psychodynamisches Grundverständnis: Ich versuche die unbewussten Bedürfnisse und Antriebe der Menschen zu verstehen, ihre Hemmungen und Ängste und alle ihre anderen verbotenen und daher abgewehrten Affekte. Ich versuche auch zu verstehen, welche unbewussten Glaubenssätze, Konzepte und Ziele einen Menschen leiten.Darüber hinaus ist er für mich bedeutsam, unter welchen Bedingungen Religion für die seelische Gesundheit und das allgemeine Wohlbefinden förderlich ist und besonders dafür, Lebenskrise oder den bevorstehenden Tod besser zu bewältigen. Eine persönliche Erfahrung hat meine berufliche und spirituelle Entwicklung entscheidend geprägt. In einer schweren persönlichen Krise, in der mir mein medizinisches und psychotherapeutisches Wissen und selbst die Unterstützung meiner Berufskollegen nichts mehr halfen, bekam ich wichtige Heilungsimpulse durch einen freichristlichen Pastor. Wenn ich zurückdenke, bin ich noch immer von der einzigartigen Qualität von Anteilnahme, Beistand und Wohlwollen beeindruckt, die ich durch ihn und andere Mitglieder seiner Gemeinde erfahren habe.

Als es mir besser ging, versuchte ich die Kräfte und Konzepte zu verstehen, die meinen Freund und Pastor für mich so hilfreich und wirksam gemacht hatten. Er selbst sah alle seine Kraft in Jesus Christus begründet. Wie er von Jesus sprach, war so persönlich, glaubhaft und bewegend, dass es mir erschien, als sei mein Freund gerade vom Mittagessen mit Jesus zurückgekommen. Mein Pastor-Freund betonte, dass er sich in einer andauernden tiefen und engen Beziehung zu Jesus befand. Ich liebte die emotionale Qualität, "die Energie", die von ihm herüberkam, und ich wünschte mir, ich könnte das noch tiefer begreifen.

Das Ergebnis meiner Suche war desillusionierend: Hinter all der faszinierenden Begeisterung und der liebevollen Anteilnahme entdeckte ich einen beinharten christlichen Fundamentalismus: Wenn du nicht ausschließlich Jesus als Gott anbetest, bist du verloren und kommst in die Hölle. Andere Religionen (selbst eine Buddha-Figur in der Wohnung) sind Götzendienst, der Islam ist Teufelswerk, das Judentum muss endlich Jesus als seinen wahren Befreier anerkennen. Unerschütterlicher Glaube an Christus und die Heilige Schrift, intensive Gebete und die Kraft des Heiligen Geistes gelten als die besten und manchmal einzigen Heilmittel und Lösungen für nahezu jedes Problem.

Angesichts dieser irritierenden Erfahrungen wurde für mich die Frage eines zeitgemäßen Jesus-Bildes immer wichtiger. Entsprechend erfreut war ich, als ich nach langer Suche Chiltons überzeugende Rekonstruktion des Lebensweges und der Persönlichkeit von Jesus las. Chilton beschreibt Jesus als ugewöhnliche, aber eben doch ganz menschliche Persönlichkeit mit einer durch und durch menschlichen Karriere. Chilton liefert schlüssige rationale Erklärungen: für die Heilungen und Wunder, die Jesus vollbrachte, und selbst für seine Verklärung und seine Auferstehung. Trotzdem leugnet Chilton nicht die Existenz eines parallelen Universums, einer Wirklichkeit, die über das hnausgeht, was wir wahrnehmen und verstehen können.Jesus wollte nie eine neue Religion erschaffen. Als Galiläer war ihm Loyalität gegenüber der Torah ins Erbgut geschrieben. Alles was er lehrte und praktizierte gründete vollständig in seinem jüdischen Hintergrund, insbesondere in der galiläischen Tradition mündlich überlieferten religiösen Wissens, das Jesus tief verinnerlicht hatte. Dennoch wird in Chiltons Buch deutlich, dass mit der Zeit in Jesus und in seiner Bewegung etwas fundamental Neues emergierte, nämlich das, was wir heute "Inklusion" nennen. Das zeigt sich eindeutig darin, dass Jesus die am meisten verachteten Mitglieder der jüdischen Gesellschaft zum gemeinsamen Mahlzeiten einlud, was im Judentum seiner Zeit beispiellos war.

Emergenz von Inklusion

Chilton stellt ein hohes Maß an Evidenz her, dass Jesus ein "mamzer" war, ein Kind zweifelhafter Vaterschaft. Seine Eltern, Joseph und die dreizehn-jährige Maria, hatten miteinander geschlafen, bevor ihre Ehe öffentlich anerkannt worden war. Infolge dieser unrechtmäßigen Zeugung hatte Jesus einen extrem schwierigen Status in dem kleinen Dorf Nazareth. Dadurch wurde Jesus besonders mitfühlend für alle Arten sozialer Ausgegrenztheit. Er war hoch sensibel dafür, was es bedeutet, vom sozialen Leben ausgeschlossen zu werden. Er brach schließlich mit der Tradition und wagte - gegen alle inneren und äußeren Hindernisse - etwas Ungehöriges: Er feierte gemeinsame Mahlzeiten mit Menschen, die als unrein galten.

Chilton wörtlich: "Jesus sprach aus persönlicher Erfahrung; er hatte selbst Armut, Hunger, den Verlust eines beschützenden Vaters und Ausgrenzung kennen gelernt. Er wusste: wer ausgebeutet und alleine ist, ist besonders bereit, sich mit der tragenden Kraft von Gottes Barmherzigkeit zu identifizieren. Die Armen, Hungrigen und Ausgestoßenen waren die Adressaten von Jesus. Viele waren gewissermaßen Unberührbare, die von frommen Juden als unrein angesehen wurden. Trotzdem aß und trank Jesus mit ihnen. Oft wird er für sein Verkehr mit Steuereintreibern und Huren angegriffen, zumal er behauptet, dass Gott diesen Leuten den Vorzug gebe.

Für Jesus waren alle Israeliten und auch ihr Land bereits rein. Er widersprach der vorherrschenden Meinung der Pharisäer, dass Reinheit erst errungen werde müsse. Er lehrte: "Es gibt nichts außerhalb des Menschen, dass in ihn eindringen und ihn beflecken könnte, sondern was aus einem Menschen herauskommt, befleckt ihn." Jesus nutzte die angeborene Reinheit von Galiläa und seiner Bevölkerung, um die Anwesenheit Gottes bei ihrem Mahlzeiten anzurufen. Zusammen zu essen und trinken bedeutete, das Reich Gottes in ihrer Mitte zu feiern und sich daran zu erfreuen. Mitgefühl breitete sich bei diesen feierlichen Mahlzeiten aus, und die Teilhabenden erfuhren Vergebung und Angenommenensein von von Gott.

Laut Chilton veränderte sich die Bedeutung der Mahlzeiten in der letzten Phase von Jesu Wirken. Nach Jahren der Auseinandersetzung mit aramäischen Quellen und anthropologischen Studien von Opferpraktiken stellt sich Chilton dem traditionellen Verständnis des Abendmahls entgegen und kommt zu dem Schluss: "Die Mahlzeiten waren Jesu letzte, verzweifelte Gebärde, dass seine eigenen Mahlzeiten eine bessere Opferpraxis darstellten als der korrupte Tempelkult. Wenn Jesus von seinem 'Blut' und 'Fleisch' sprach, bezog er sich in keiner Weise auf sich selbst. Er meinte, dass sein Mahl in Wirklichkeit ein Opfer geworden sei. Wenn Israeliten Wein und Brot teilten und damit ihre eigene Reinheit und die Gegenwart des Reiches Gottes feierten, würde sich Gott daran mehr erfreuen als an dem Blut und Fleisch auf dem Altar im Tempel."

Für Chilton kann Jesus nicht gemeint haben: “Hier ist mein persönlicher Leib und mein persönliches Blut.” Eine solche Interpretation würde nur Sinn machen, wenn sich Jesus von Judentum abgewendet hätte (wofür es keinerlei Hinweise gibt). Die einzige (Sinn machende) Bedeutung seiner Worte ist, dass Wein und Brot das Brandopfer (von Tieren) im Tempel ersetzen sollten.

Warum wurde Jesus gekreuzigt?

Die Mitglieder des Sanhedrin, des Hohen Rates und höchsten Gerichts des jüdischen Volkes, nahmen wie andere fromme Juden in Jerusalem Anstoß an den skandalösen neuen Praktiken von Jesus. Er hatte seine Mahlzeiten zu einem Altar gemacht, der mit dem Altar im Tempel konkurrierte. Der Jerusalemer Tempelkult war wirtschaftlich für die Römer ebenso wichtig wie für die jüdische Priesterkaste. Sie durften Jesus nicht erlauben, ihn herabzuwürdigen. Außerdem hatte Jesus zum Widerstand gegen die Bezahlung der üblichen Tempelsteuer aufgefordert. Seiner Meinung nach sollte der Tempel nicht mit Geld, sondern mit eigenhändigen Opfern unterstützt werden (er folgte dabei einer Prophezeiung des Sacharja, die er entschlossen war zu erfüllen) .Das alttestamentarische Buch Sacharja sagt im Kapitel 14 voraus, dass sich Gottes Königtum auf der ganzen Erde in dem Augenblick zeigen würde, wenn Israeliten zusammen mit Nicht-Juden ihre Opfer im Tempel darbieten würden. Weiterhin wurde prophezeit, dass diese Betenden ihre Opfer selbst, in galiläischer Art, ohne Mittelsmänner (Priester) darbringen würden. Das Buch versprach auch, dass “es niemals wieder Händler im Heiligtum des Herrn der Heerscharen geben werde (14:21). Opferungen im Tempel würden ein universelles Fest mit Gott sein, offen für alle Völker, welche die Wahrheit annahmen. Jesus glaubte, dass die Apokalypse bald kommen würde und dass die Welt, wie er sie kannte, enden würde.

So surreal, wie die Apokalypse des Sacharja vielen von uns erscheinen mag, sie veränderte die Geschichte, wenngleich nicht in der Weise, wie Jesus dachte. Chilton macht klar, dass Jesus eine ernste Bedrohung für die herrschende Klasse geworden war. Schon seine Macht, Dämonen auszutreiben und zu heilen, hatte Anlass gegeben, ihn mit den Größten von Israels Propheten zu vergleichen, z.B. mit Elia, der den Sohn einer Witwe zurück ins Leben gebracht hatte. Das Andenken an Elia während der neun Jahrhunderte vor unserer Zeitrechnung war immer verbunden gewesen mit seinem Widerstand gegen König Ahab und dessen Gewogenheit für fremde Gottheiten. Auch Herodes Antipas, in dessem Herrschaftsgebiet Jesus lebte, war just solch ein Kollaborateur (mit den Römern). Er war bereits von Johannes dem Täufer herausgefordert worden und hatte mit tödlicher Gewalt reagiert. Nun war er auf Jesus aufmerksam geworden und wusste um dessen Verbindung zu Johannes.

Jesus glaubte, mit prophetischer Autorität zu sprechen und zu handeln. Propheten vom Schlag eines Elia konfrontierten die Herrscher dieser Zeit mit der Drohung göttlichen Urteils, die durch Zeichen bestärkt wurde. Elias Autorität war durch seine prophetischen Taten bestätigt worden, die oft destruktiv waren: Er bewirkte Dürre und Flut (1 Könige 17:1–7; 18:41–46), rief Feuer vom Himmel herab um ein Opfer zu verzehren (1 Könige 18:25–38), und tötete die Propheten des Baals (1 Kings 18:39–40). Elias ermutigten zur Revolution im Namen Gottes. Im ersten Jahrhundert glaubten viele Juden, dass Gott Elia erneut aussenden würde.

Das erste Jahrhundert sah viele Männer, die Elia zu ihrem Vorbild wählten. Sie versprachen ihren Anhängern ein Zeichen, dann eine Revolution. Wenn immer ein solcher Möchte-gern-Prophet das versprochene Zeichen ankündigte und zu einer bewaffneten Rebellion gegen Rom aufrief, reagierte das Imperium rasch und tötete den prophetischen Aspiranten, bevor dieser sein versprochenes Zeichen ausspielen konnte. Kein öffentlich gefeierter Prophet war nur eine religiöse Figur, sondern eine potenzielle militärische Bedrohung. Auch Jesus und seine Anhänger schienen als potenzielle Armee, als eine Bande von revolutionären Unruhestiftern. Galiläer verglichen Jesus mit Elia, und sein Ruf, ein Prophet zu sein, wertete Antipas als eine größere Gefahr als die, die zuvor von Johannes dem Täufer ausgegangen war.

Unter den Anhängern von Jesus waren viele begeisterte Galiläer, die hofften, dass sie durch Jesus mächtig genug werden würden, um in den Tempel einzudringen und das Land von Herodes Antipas und den Römern zu befreien. Chilton glaubt, dass es nicht nur visionäre Inbrunst war, die Jesus nach Jerusalem trieb, obwohl er wusste, dass dieser Schritt gefährlich war. Da war auch eine realistische Seite. Indem er die Prophezeiung des Sacharja in die Tat umsetzen würde, hoffte er, dass sich alles ohne militärische Revolte verändern würde. Er würde die zerlumpte Bande von Galiläern in den Tempel führen, um ihr galiläisches Opfer auf den Altar zu legen. Gott würde dazu bewegt werden, wieder in die Geschichte Israels einzutreten, und sein Königreiche würde kommen. Ohne es zu wissen, war Jesus im Begriff nach Jerusalem exakt in jenem Augenblick zu kommen, in dem sich der Tempel in einen Marktplatz verwandelt hatte.

Kaiaphas, Israels Hoher Priester, hatte erst kurz zuvor den Umzug der Jerusalemer Verkäufer von Opfertieren vom Ölberg in den Tempel angeordnet. Diese Maßnahme diente dazu, die Tiere nach ihrem Verkauf vor Verletzungen zu bewahren, die sie sich auf dem Weg zuziehen konnten und die dazu führen konnten, dass die Tiere nicht mehr die strengen Kriterien erfüllten, um für die Opferung zugelassen zu werden (außerdem war es im Durcheinander der Herden schwierig zu erkennen, welches Tier das eigene war). Doch den Pharisäern und den meisten anderen Juden war der Handel im Tempel ein Gräuel. Die Pharisäer bestanden darauf, dass die Opferhandlung im Tempel eine nicht kommerzielle Begegnung zwischen dem Volk Israel und Gott sein müsse.

Als Jesus Anfang Herbst 31 den Tempel betrat und das geschäftige Treiben der Verkäufer im großen Hof sah, empfand er einen katastrophalen Widerspruch zur Prophezeiung des Sacharja. Wie konnten er und seine Anhänger das finale, apokalyptische Opfer, das Sacharja vorausgesagt hatte, in einem Tempel inszenieren, der entweiht worden war? Drei Tage später kam er mit seinen Unterstützern, 150 bis 200 Männern, wieder. Seine Anhänger warfen die Tische der Händler um, ließen die Vögel frei, banden die Tiere los und trieben sie mit den Händlern aus dem Tempel hinaus. Einige wurden geschlagen und getreten. Es gab mindestens einen Mord an einem Händler durch Barabbas, einen der vielen gewalttätigen Streiter, die sich Jesus angeschlossen hatten.

Die Tempelreinigung machte Jesus zum Helden. Eine große Zahl von Juden war gegen den von Kaiaphas befohlenen Umzug der Verkäufer in den Tempel und zeigte Sympathie für die Besetzung des Tempels durch Jesus. Vor allem hatte er mit seinem Akt Galiläer angesprochen: Jesus sprach die Sprache ihrer Revolution, die sich auf den Akt des Opferns konzentrierte. Monate später, im Jahr 32, kam Jesus erneut nach Jerusalem zurück, gleichzeitig mit Tausenden frommer Juden, die zum Passah-Fest in die Stadt strömten. Viele Pilger hatten von Jesus gehört und schlossen sich ihm an. Der Marsch glich einer Prozession und wurde zu einem ekstatischen Ereignis. Die Menge schrie ihre Erwartung des nahen Kommens des Reiches Gottes heraus, von dem sie wussten, dass es Jesu zentrales Anliegen war.

Dabei spielte Jesus bewusst die Karte seiner Abstammung aus dem Hause David aus, die er durch seinen Vater Joseph beanspruchte. Als Sohn Davids, einem weisen, heilenden Herrn über Dämonen in der Erblinie von Salomon, führte Jesus jetzt die wachsende Zahl seiner Anhänger, zu der inzwischen auch sein Bruder Jakobus gehörte, zum Zionsberg. Obwohl es Jesus ausschließlich um das Opfer im Tempel ging und nicht um eine militärische Revolte, gaben sich einige seiner Anhänger noch immer der Hoffnung hin, seine Absicht würde eine direkte Aktion gegen Rom und seine Handlanger einschließen. Für Kaiaphas stand ein neuer galiläischer Aufstand im Tempel unmittelbar bevor. Seine Polizeitruppe war nicht stark genug, um die gewalttätige Reaktion zu kontrollieren, auf die er gefasst sein musste, falls er versuchen würde, Jesus zu verhaften. Er wendete sich an den römischen Prokurator Pilatus und überzeugte ihn, dass Jesus nicht nur ein harmloser Spinner war. Kaiaphas beschuldigte Jesus, der Initiator einer illegalen Bewegung gewalttätiger Opposition zu sein. Jesus sollte mit römischer Hilfe verhaftet werden.

Das Todesurteil

Jesus hatte wiederholt Konflikte mit Pharisäern und Priestern provoziert. Die Pharisäer hatten ihm seine Tischgemeinschaft mit Leuten vorgeworfen, die aus ihrer Sicht unrein waren. Jesus wurde wiederholt angegriffen, den Sabbat nicht einzuhalten sowie die Reinheitsgesetze für die Speisen und Rituale während der heiligen Feste nicht zu respektieren. Er hatte sogar eine größere spirituelle Autorität als die der Pharisäer und Priester für sich beansprucht. Aber Jesus hatte sich keine wirklich nachweise Lästerung gegen den Tempel oder die Tora zu Schulden kommen lassen. Nie hatten seine Worte das, was dem Judentum heilig war, verletzt. Die Anklage gegen Jesus erzwang nicht notwendigerweise die Todesstrafe.

Außerdem hatte Jesus unter den Pharisäern und sogar innerhalb des Hohen Rats einige Anhänger. Nikodemus, ein

Mitglied des Hohen Rats, stellte fest, dass es keine handfesten Anklagepunkte gegen Jesus gäbe.

Es war für Kaiphas nicht leicht, die Verurteilung von Jesus zu rechtfertigen.

Jesus hatte während der Tempelreinigung von einer "Räuberhöhle" gesprochen. Vielleicht ist ihm genau das zum Verhängnis geworden. Er hatte sich dabei auf Jeremia (7,11) und dessen Prophezeiung der Zerstörung des Tempels bezogen, was leicht zu der Behauptung verdreht werden konnte, dass sich Jesus den Untergang des Tempel wünschte. Kaiaphas und seine Anhänger arbeiteten mit genau dieser Verzerrung, um Opposition gegen Jesus zu schüren. Doch selbst solche Prophezeiungen waren kein Kapitalverbrechen. Daher konzentrierte sich Kaiaphas auf eine grundlegendere Frage: "Lehrst du, dass deine Feiern der Tischgemeinschaft das Tempelopfer ersetzen, weil du Gottes eigener Sohn bist?" Jesus antwortete: "Ich bin es, und du wirst den Menschensohn sehen, der zur Rechten der Macht sitzt und mit den Wolken des Himmels kommt!"

Chilton glaubt: "Schweigen an dieser Stelle hätte Jesus sein Leben retten können, aber nicht einmal gegenüber dem Hohepriester legte Jesus seinen Eigensinn ab." Jesus hatte mit seinen eigenen Lippen gesagt, dass seine Gott gegebene Autorität größer war als die von der Tora verliehene Autorität der Hohepriester. Die Theologie des Judentums des ersten Jahrhunderts war eindeutig: Ein Angriff auf eine von Gott gerechtfertigte Institution verunglimpfte den Gott Israels selbst und forderte göttliche Vergeltung heraus, entweder direkt oder durch die Entscheidungen israelischer Gerichte. Selbst unter den Anhängern von Jesus war Judas nicht der einzige, der eine so direkte Herausforderung der jüdischen Tradition missbilligte und Jesus verließ.

Jesus hatte während der Tempelreinigung von einer "Räuberhöhle" gesprochen. Vielleicht ist ihm genau das zum Verhängnis geworden. Er hatte sich dabei auf Jeremia (7,11) und dessen Prophezeiung der Zerstörung des Tempels bezogen, was leicht zu der Behauptung verdreht werden konnte, dass sich Jesus den Untergang des Tempel wünschte. Kaiaphas und seine Anhänger arbeiteten mit genau dieser Verzerrung, um Opposition gegen Jesus zu schüren. Doch selbst solche Prophezeiungen waren kein Kapitalverbrechen. Daher konzentrierte sich Kaiaphas auf eine grundlegendere Frage: "Lehrst du, dass deine Feiern der Tischgemeinschaft das Tempelopfer ersetzen, weil du Gottes eigener Sohn bist?" Jesus antwortete: "Ich bin es, und du wirst den Menschensohn sehen, der zur Rechten der Macht sitzt und mit den Wolken des Himmels kommt!"

Chilton glaubt: "Schweigen an dieser Stelle hätte Jesus sein Leben retten können, aber nicht einmal gegenüber dem Hohepriester legte Jesus seinen Eigensinn ab." Jesus hatte mit seinen eigenen Lippen gesagt, dass seine Gott gegebene Autorität größer war als die von der Tora verliehene Autorität der Hohepriester. Die Theologie des Judentums des ersten Jahrhunderts war eindeutig: Ein Angriff auf eine von Gott gerechtfertigte Institution verunglimpfte den Gott Israels selbst und forderte göttliche Vergeltung heraus, entweder direkt oder durch die Entscheidungen israelischer Gerichte. Selbst unter den Anhängern von Jesus war Judas nicht der einzige, der eine so direkte Herausforderung der jüdischen Tradition missbilligte und Jesus verließ.

Die Entwicklung der besonderen mystischen Spiritualität von Jesus

Die (sehr zeitaufwendige) deutsche Übersetzung werde ich gerne fortsetzen, falls das von den Lesern meines Blogs gewünscht wird. Bitte setzen Sie sich mit mir in Verbindung.Over time Jesus developed a particular mystical kind of spirituality. According to Chilton the mystical quality of Jesus' spirituality explains both the miracles he performed, and the experience of the resurrected Jesus, that many of his followers shared after his death. Chilton considers the ostracism and the forlornness that Jesus faced as a child as important factors for his spiritual development. Chilton imagines a small child, standing apart from other children, wishing to play but not being included, defensively ironic about the gang’s incapacity to agree on a game. Jesus must have spent much of his time alone. All the insults explain why Jesus came to see God as his father, his Abba in Aramaic. If Joseph’s fatherhood was in doubt, God’s fatherhood was not.

Chilton explains that Jews of this time recognized themselves as God’s children and addressed God as "our father, our primordial redeemer is your name" (Isaiah 63:16). To call God "father" signified that the creator of the entire world had entered into a special relationship with Israel, as a father to his children. And Jesus joined some rabbis in a further, bolder claim, asserting God’s personal, fatherly care for his children as individuals. Aramaic stories in the Talmud show that "father" was a Jewish way of referring to God, and when Jesus was a rabbi he instructed his students to pray regularly to God as Abba. The divine relationship became particularly intimate with Jesus.

From the age of ten, when Jesus had joined his biological father travelling as a journeyman he got in contact with the variety of folk tales and different unique ways of rendering Scripture in its Targum (the Aramaic word for “translation”). Targums are paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible translated in Aramaic. They represent the oral “Torah on the lips,” what Jesus and the other illiterate Jews (the majority of the Israelites of his time) used. A Targum was not a mere verbatim translations of the Hebrew texts. Those who memorized, translated and recited the oral Scripture added whole paragraphs and paraphrased long sections. Targums were the foundation of the faith of the ordinary people. According to Chilton they are the key to understand Jesus’ Judaic orientation and the vocabulary of his teachings.

Later Jesus became a master of the rich oral traditions of Galilee. He improvised with their themes and created so many parables and metaphors. The Kingdom of God was the pivotal hope of Galilean Judaism. Jews believed that God ruled them and that one day his Kingdom would be the only power on earth and in heaven. The Hebrew Bible claims that God helps his chosen people conquer their enemies when they keep his covenant, and lets them fall victim to oppression when they stray from righteousness. Many Galileans believed that if they lived in accord with God’s commandments and prohibitions, God would drive the Romans out from Israel and institute a reign of justice.

The Kingdom of God became the principal theme of Jesus’ message throughout his adult life. When his father Joseph died, the Kingdom of God was the only support and the only thing for which Jesus yearned at the core of his broken heart. Jesus' Jewish tradition saw God’s immanence everywhere, in the force of a mustard seed and yeast. Later, as a rabbi, he saw the divine Kingdom in how one person relates to another. Chilton suggests that even as a child, Jesus had a direct intuition of how his Abba, moment by moment, was reshaping the world and humanity. Like other great religious teachers, emotions led Jesus to an insight put into words only later.

Chilton claims that already as an teenager (during a visit in the Temple of Jerusalem) Jesus abandoned his family and the daily suffering from disdain in Nazareth. He joined John the Baptist (Yochanan the Immerser), a famous rabbi known to offer ritual purification in the Jordan River. For Chilton John is the key to Jesus’ crucial teenage years. Jesus wanted to learn John's way of living God’s covenant with Israel. John's disciples were willing to endure hardship and deprivation, passionately seeking the way that brought access to God. They lived in the wilderness, supporting themselves by food that grows of itself, washing with cold water day and night. When repeatedly immersed by John the hurt of Jesus' childhood, being an outcast, was healed. Jesus gained a place in a respected religious group.

John initiated Jesus into the esoteric side of his teaching. John's path into the mysteries of the divine mind was a part of the ancient rabbinic tradition. It focused on the first chapter of Ezekiel that describes the Chariot, the moving Throne of God, the source of God’s energy and intelligence, the origin of his power to create and destroy. By meditating on the Chariot, John and his disciples aspired to become one with God’s Throne. Already Moses had seen God's Throne during an ecstatic vision while receiving the Torah. The Throne appears again with Elijah's transport into heaven. The Chariot became the master symbol of Jewish mysticism.

The majority of rabbis in the ancient period, Jesus included, were illiterate. Ezekiel’s words had to be memorized in all details. The initiate’s meditation had to be on the text’s meaning, not on the mechanics of recitation. The disciples also had to master the text’s intonation and cadence. The musical phrasing of the words (like mantras in Hindu and Buddhist traditions) was deemed essential to clear the way for divine realization. The words themselves were viewed as sacred, imbued with divine force. Jesus learned to become Ezekiel’s text, embody its imagery, and master the many other complex texts within Jewish tradition that embellished, augmented, and refined Ezekiel’s vision. Like any aspiring rabbinic visionary, he needed a superb memory and concentrated devotion to pursue his quest.

John was like a guru. His voice, his attitude, posture and gestures during the meditations, his intense mindfulness and ecstatic vision were as much the text that Jesus learned as the words from Ezekiel. Jesus learned the secrets of God’s Spirit, which flowed from the Chariot through all creation. John promised his disciples that just as he had immersed them in water, God would immerse them in holy Spirit. Immersion in Spirit would not only lead to repentance and release from sin but also overcome the basic prophetic criticism of Israel: the lack of compassion and disregard one Israelite showed another. John expected that God’s Spirit was ready to be poured out on Israel anew as it had been at the time of Moses. John and then Jesus were seen as prophets inspired (literally “breathed into”) by Spirit and speaking directly on God’s behalf.

Jesus believed that the holy Spirit was upon him and that he spoke for God. Repetitive, committed practice, diet, exposure to the elements and repeated immersions intensified his vision of God's Chariot and made him have a vivid vision of the heavens splitting open and God's Spirit descending upon him as a dove: "You are my beloved son, in you I take pleasure." Jesus related his experience of Spirit to his friends, and John and his disciples embraced it as the beginning of the fulfillment of God’s promise. Expressing deep affection John called Jesus “the lamb of God”, because in his innocence he embodied both release from sin and the arrival of Spirit. Jesus received from his fellow visionaries the first sign of the special role he would play in Israel’s destiny. Some of John’s disciples said they themselves had heard the voice that spoke to Jesus. Their communal vision welded them together.

As Jesus grew older and more confident, his ability to invoke Spirit and the power of his vision of God’s Throne made him increasingly successful in gathering pilgrims for immersion. Jesus started to move into settled areas, where he could immerse more people than John did. Jesus was convinced that the people he invited to cleanse themselves by immersion were already clean. That was why he could eat with them. Eating with people was vivid testimony that one considered them to be pure. Jesus joined in holy feast with them. He spoke of the Abba of all who was the source of Israel’s blessing: “Abba, your name will be sanctified, your Kingdom will come.” Jesus gradually replaced immersion with communal meals as the ritual symbol of the coming Kingdom of God.

Sporadic and short-lived retreats allowed Jesus constant meditation on the Chariot in which he found solace. Chilton claims that Jesus began to use a vision from the book of Daniel, an angel with an human face standing beside the Throne of God, called in Aramaic “one like a person”, engaged in a cosmic battle with the angelic representatives of the great empires that had conquered Israel. The “one like a person” brought Jesus close to his Abba and became the anchor of his visions. Jesus and his disciples identified themselves with the “one like a person”, what can also be translated as “son of man”. In Daniel’s vision, God himself intervenes and elevates "the one like a person" within the heavenly court.

In the mystical tradition of Judaism of this time, a vision of the Chariot was also called an entry into Paradise, the original Garden Eden of Genesis. Jesus entered consuming trances, and saw faith as a means by which people could share his vision of Eden, and be transformed by its eternal vitality. His healings effectuated the restoration of the Paradise that was part and parcel of God’s primordial intent in making the world. Jesus began to insist that his disciples have the same kind of faith in him that they had in his Abba. This was an outgrowth of his identification with the “one like the person.” Jesus had begun to see himself as part of the heavenly court.

On Mount Hermon Jesus was transformed before Peter, James, and John into a gleaming white figure, speaking with Moses and Elijah. Years of communal meditation made what Jesus saw and experienced vivid to his disciples too. Covered by a shining cloud of glory, they heared a voice say: “This is my son, the beloved, in whom I take pleasure: hear him.” When the cloud passed they found Jesus alone as God’s son. The voice did not make Jesus into the only (and only possible) “Son of God” like the later doctrine of the Trinity. Rather, the same Spirit that had animated Moses and Elijah was present in Jesus and could be passed to his followers, each of whom could also become a “son” (like in Buddhism principally everybody following Buddha's path can become a Buddha).

According to Chilton the story of the Transfiguration represents the mature development of Rabbi Jesus’ teaching. He had led his disciples into the richness of the vision of the Chariot by sharing his vision with them and transforming them. His teaching shifted away from what can be discerned of God’s Kingdom on earth to what can be experienced of the angelic pantheon around God’s Throne. It must have seemed to the apostles at that moment that all the hardships, struggles, and disappointments were finally rewarded in the intimacy he gave them with the divine presence.

Jesus’ advanced esoteric teaching

For Chilton the most difficult part of Jesus’ science of approaching the Throne is expressed in Mark 8:31–33, Matthew 16:21–23,and Luke 9:21–22: "And he began to teach them that: The one like the person must suffer a lot and be condemned by the elders and the high priests and the letterers and be killed and after three days arise." Here the Aramaic phrase “one like a person” is used to designate ordinary human beings. Rather than a precise foreknowledge of Jesus' imminent death (a later distortion of its meaning) this text conveys Jesus' deep sense that all of us must remain aware of our frail, suffering nature in the midst of the vision of the Throne and its angels. One faces Abba with a child’s vulnerability.

For Chilton one of the pitfalls of

any spiritual discipline is that the practitioner might exalt his own

importance, claiming to be as infallible and powerful as the divine world he

trains himself to see. Forgetting our mortality betrays God, and we run the

risk of supplanting God’s majesty with our own arrogance. Jesus insisted on conscious

acceptance of suffering. Jesus did not treat pain as a virtue in itself, but

turned the endemically human experience of suffering into a means of

discovering divine power in the midst of our own weakness. Danger and suffering

were to be embraced as signs that God’s Kingdom was making its way into a world

that resisted transformation:

"For whoever wishes to save

one’s own life, will ruin it, but whoever will ruin one’s life for me and the

message will save it. For what’s the profit for a person to gain the whole

world and to forfeit one’s life? Because what should a person give for

redemption of one’s life? For whoever is ashamed of me and my words in this

adulterous and sinful generation, the one like the person will be ashamed of

also, when he comes in the glory of his father with the holy angels" (Mark

8:35–38; Matthew 16:25–27; Luke 9:24–26).

The disciples learned that putting

their lives in jeopardy enabled them to stand before the heavenly Chariot with

the one like the person. Jesus reminded them that the prophets of Israel had

suffered for the sake of their vision and for the reward of the vision of God.

He insisted that his followers learned humility, of what he set them an example

in the way he lived. He taught them to recognize that one is limited, weak, in

need of nurture and forgiveness in the presence of the creator of all things. Jesus’

execution became the vehicle for an unconquerable vision. The “cross” he

expected to carry, and expected each of his followers to carry, symbolized the

potential of suffering to serve as the gateway from this world to the realm of

God.

The vision of the resurrected Jesus

The promise of resurrection was unequivocally

articulated in the book of Daniel, one of the Hebrew Bible’s latest works: “Many

of those who sleep in earth’s dust shall awake." Priestly Zadokites argued

that the Torah did not require belief in resurrection, some Pharisees insisted

that one was raised from the dead in the same body in which one had died.

Against the Zadokites, Jesus found the resurrection hope within the Torah

itself, in its reference to the enduring lives of the patriarchs. Against the

Pharisees, he compared the resurrected patriarchs to angels. He never stated

that the dead are raised physically, in the same bodies they had at death. For

Jesus resurrected humans were like angels in the heavens.

For Jesus the transformation from a

physical to an angelic state was the substance of resurrection and inextricably

rooted in a Semitic understanding of human life and personality. The Hebrew word

"nephesh", meaning both life and breath, coordinated body and

breathing within a single, living whole. Nephesh was linked categorically to

the view that God was Spirit, the almighty force of wind breathing life into

all creation. For Jesus human beings could shape their innermost breath, the

pulse of their being as well as their cognitive awareness of the Chariot, to

correspond to the overpowering creativity of divine Spirit. Jesus focuses us on

the essence of our humanity, and allows us into his parallel universe, imbued

with the justice and glory of God. The resurrection is both the most elemental

and the most difficult to grasp of all Gospel teachings. And yet the confidence

that God raises life from death, is still sustaining Christianity.

Chilton suggests a rational

explanation for the disciples' experience of the resurrection of Jesus: Like

Buddha, Jesus was a superb teacher, capable of imparting the inner energy as

well as the outer form of the religious wisdom he had discovered. The disciples’

mystical practice of the Chariot only intensified after Jesus’ death, and to

their own astonishment and the incredulity of many of their contemporaries,

they saw him alive again. The fear and pressure due to Jesus’ crucifixion

intensified his followers’ experience of his angelic persona and their vision

of the spirit world where they, like he, increasingly dwelled. The resurrected

Jesus appeared to them in vision, alive in the glory of the Throne but

profoundly changed. At times, they didn’t even recognize him.

According to Mark (16:1–8) Miriam

Magdalene, Miriam of Yaaqov and Shalome, were the first to have this visionary

experience. Mark speaks of the women's “trembling and frenzy”. Fear and ecstasy

were typical emotions related to the vision of the divine. The angelic young

man the women encountered in the empty tomb signaled that they had entered the

trance world of the Chariot. When he said in the majestic rhetoric of Luke,

“Why do you seek the living among the dead?”, the event we call the resurrection

was born. When Jesus' followers met together, meditated, and prayed, their

journey into the world of the Chariot brought them face to face with Rabbi

Jesus. Chilton suggests that their collective visionary trances engendered a

form of religious hysteria.

When Jesus' disciples returned to

Jerusalem for the great feast of the Pentecost, the wheat harvest, which

occurred seven weeks after Jesus' death at Passover, they gathered privately in

festal meals. They had many experiences of the resurrected Lord what made them

feel vindicated and reenergized. In their understanding, the risen Jesus poured

out on them the same Spirit he had been immersed in since his time with John. The

New Testament records that five hundred other followers in Galilee also saw the

rabbi raised from the dead. Jesus appeared in distant places nearly

simultaneously and walked through doors. He insisted that Miriam of Magdala kept

her hands off him, but invited Thomas to finger his wounds? To understand these

confusing accounts Chilton suggests to see the resurrection as an angelic,

nonmaterial event.

In Paul’s first letter to the

Corinthians, written around 56 C.E., he listed twelve delegates, the five

hundred “brethren” of Jesus, James, Peter, other apostles, and himself, as having

experiences of the risen Jesus. Paul’s own resurrection vision occurred in 32

when he was still named Saul. On a mission from Caiaphas to denounce Jesus’

followers in Damascus he was suddenly surrounded by light. A heavenly echo

identified itself as Jesus of Nazareth. For Chilton this was in no sense a

physical encounter with Jesus. The appearance is depicted very similar to what Jesus'

disciples experienced, complete with prophetic commissioning and the symbolism

of the holy Spirit in the surrounding light.

Saul turned around. After a retreat

into solitude for three years he went back to Jerusalem. He spoke about his

vision only to Peter and James. Chilton holds that Paul understood that his

experience was more visionary than physical, as he carefully says in a passage

of straightforward Greek that has been perennially mistranslated as "God took

pleasure to reveal his son to me.” According to Chilton the correct

translations is “God took pleasure to uncover his son in me” (Galatians

1:16). By distorting the meaning of a single preposition, traditional

Christianity has falsified its premier apostle’s own visionary experience of

what he explicitly (1 Corinthians 15:8) understood to be the resurrected Jesus.

The meaning of what we know about Jesus for our own life and death

According to Chilton's experiences

with terminally ill patients, a little Golgotha awaits us all at the close of

our lives in one way or another. "Fear sometimes makes us wish for a

quiet, sudden and even violent end, rather than confront that inexorable and

unyielding moment. But trying to evade the instant when we truly and completely

lose ourselves only compounds pain with delusion." Standing by the graves

of the people Chilton burries, he is aware that a person has passed beyond our

reach. "Here we know that we all, too, are broken. But Spirit does not

die. (…) The sacrifice of our own lives frees Spirit to fly across the heavens.

There is no one way to die, as there is not a unique wisdom of what dying

means, or a single cross we all have to bear." For Chilton Jesus' "discovery

of who we are in our pain, offers the vision that death’s change is not simply

degradation and despair. It is not the end of us, but the end of who we think

we are. To lose one’s life is to save it. Death is our hardest lesson, but it

is also the gateway into the true, divine source of human identity."

I would like to add some aspects:

Jesus life, as Chilton depicts it, is a fascinating story of human struggling,

development, triumph, error, and failure. Jesus was able to transform his

suffering into compassion and visions. He consequently lived his visions. His

devotedness was complete. He gave thousands of underdogs comfort, hope, self

confidence, and orientation. He resisted the temptation to head a violent upheaval.

Instead he trained his followers to experience a parallel world of divine

peace, justice, and glory. He taught them to trust in it and to transform their

intrinsic fervor for God into care for their neighbors and even into love for

the enemies. He acted as a trustworthy model for what he taught. He

successfully opposed the rigid positions and practices of the powerful and

established new spiritual concepts and rituals that better suited the needs of

the indigents and social outcasts. He left such a strong impression on his

followers that after his death his movement rather than vanishing lived up to

its full potential.

What made Jesus that effective and influential?

How

come an illiterate construction worker from a petty province of the Roman

empire crucially changed history? Was it his divine nature,

was he part of a divine plan as it is taught in churches? Like other great

religious personages, Jesus must have had a particular sensitivity and

receptivity for the reality beyond what we can perceive with our ordinary

senses and what we can grasp with our usual reasoning. He must have had a

particular visionary capacity. He did not only repeat and elaborate the

patterns of his culture, like the Pharisees did, but he generated – always

based on his Judaic background – novel, advanced and realistic ideas and

practices. He was a great reformer of Judaism, maybe the most important. It is

not seriously conceivable that Jesus intended to create a new religion apart

from Judaism.

Chilton's book suggests that the

evolution of early Christianity was not the outcome of the ministry of a single

unique person, but an interactive and reciprocal group effect, to which many

contributed and for which the time was ripe. When John the Baptist had been

executed his disciples had scattered. Some had joined Jesus. Surprisingly

Jesus' death and failure at the cross turned out to be crucial for the unswerving

and unstoppable process of future development of his movement. Obviously Jesus

had created an extraordinary quality of attachment and community with a part of

his followers, and also among themselves. He had bestowed on them orientation, trust

in God and in themselves, and an enormous extent of visionary enthusiasm.

Through him they had found a new assignment and meaning for their life. Already

before he died he had encouraged them to speak and act in his name.

Psychodynamic aspects of the experience of resurrected Jesus

From my psychodynamic background I

would like to suggest to view the apostles' experience of the resurrected Jesus

and of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a manifestations of a particular grief

process. Intensively trained to change their state of consciousness into a

meditative trance and to experience common visions of the divine some hundred

of Jesus' followers were able to transform their fierce longing for their

master into a collective experience of perceiving him alive.

According

to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross there are five stages of grief: denial, anger,

bargaining, depression and acceptance. In the first stage, the loss of the

beloved person is denied, the mourner thinks: "This isn't happening."

In psychodynamic terms denial can be understood as a temporarily useful defense

mechanism preventing the mourner's self organization from collapsing due to the

unexpected bereavement of an so called self object (a person that provides

emotional security and stability). The vision of the resurrected Jesus can be

considered as an expression of the apostles' transient mental state of denial.

But

the vision of the resurrected Jesus is more than just a defense mechanism. The

emotional relationship and the bonding between the mourner and the deceased

person goes on. Important aspects of the beloved person are internalized and

remain alive as a so called internal object. From the psychodynamic perspective

Jesus continued to

live within his followers as a good, stable and nourishing inner object. In a

way the apostles' experience of the resurrected Jesus represented a realistic

part of their inner truth. After forty days of collective mourning Jesus did

not appear to his followers any longer, what is called Ascension of Jesus in

the New Testament. As a rational explanation I suggest that the grief process

of Jesus' followers – facilitated by sharing the pain and sadness – had reached

a stage in which there was no further psychological need for visioning Jesus

alive and denying his death.

Psychodynamic aspects of the experience of Pentecost

Jesus had spent his last years

covert in the wilderness to evade the persecution of Herodes Antipas, the ruler

of Galilee, who had already ordered the execution of his teacher John the

Baptist. In order to go on spreading his message in Galilee, Jesus had dispatched

his disciples as his delegates. He had encouraged them to proclaim God’s Kingdom

in Galilee and to heal people on his behalf. Hence, after his death, his

followers had a lot of practice and were well prepared to continue their

master's ministry. Pentecost, more than fifty days after Jesus' crucifixion,

indicates the moment when the desperation and paralyzation of his disciples had

completely turned into new confidence and determinedness. The New Testament

depicts the recovery of the disciples' power and courage as the descent of the

Holy Spirit.

It is a natural psychological phenomenon

that, after the death of a parent or an important teacher who are role models,

the successors adopt the parent's or teacher's qualities, habits, values,

opinions, goals, visions, and even their mental power. There is a conscious or

unconscious identification with the deceased. When the evangelist John (15,4)

lets Jesus say: "Abide in me,

and I in you", it reflects the simple psychological truth, that after the

death of a beloved parent or teacher the internal attachment of his successors

persists and can even deepen, especially if over time the deceased is strongly

idealized. All religious doctrines seem to have in common that their

originators and were idealized and their objectives deformed by later

generations. It is tempting to project one's own ideas and needs onto an

idealized person who cannot defend herself any more.

How to facilitate relationship with Jesus for people of today?

Many people need a simple

concept of what is right and what is wrong. For them religious or political simplification,

fundamentalism, and intolerance towards other ethnic groups, religions and

wisdom teachings provide a feeling of stability and consistency. Those people

will not be open for Chilton's ideas. But there is a growing number of people

who are not longer reached by the established concepts and by the wording of

the churches. The traditional Christian glorification of Jesus as the only begotten

son of an all-knowing and almighty God, the teachings of virgin birth, original

sin, Holy Trinity, and much more dogmata insult the enlightened mind and do not

correspond to the everyday experience of the majority of modern people.

I am one of them. For me it

is much easier to become friend with a fully human, non-transfigured,

vulnerable Jesus who struggled, vacillated, erred, failed and missed his messianic goal of saving

Israel and establishing God's kingdom. Precisely through his glorious failure

at the cross Jesus caused the very miracle of his ministry: his frightened and

demoralized followers did not scatter and resign although the crucifixion had unequivocally

proved that Jesus was not the messiah the way most ancient Jews expected him.

There was something much more sustainable than political and military power. A

new quality of bonding, solidarity, and mutual care had emerged within the core

group of Jesus' followers. Jesus' movement provided a completely novel answer

to the feeling of collective impotence and despair of the Jewish people in the

first century C.E. and to their deathful hatred against the Roman occupiers.

What can we learn from Jesus and his followers for the challenges of today?

Today

we face an alarming rise of religious and ethnic intolerance, increasing

enmity, war and terror. Unfettered capitalism destroys the environment and the

livelihoods of millions of people. Important public, political and economical

institutions like banks, insurances, and other big business concerns, even the

press and the political system do not seem trustworthy any more to many people.

There is also a growing social isolation and loneliness of millions of

individuals. There is a loss of trust, solidarity and mutual care even in

private relations. The material abundance that capitalism engendered taught us

that the full satisfaction of our material needs does not automatically create

happiness. In contrary many people in the wealthy western countries suffer from

overweight, addiction, prosperity diseases, pressure to perform, burn out,

depression, anxiety and psychosomatic disorders.

The

recovery of trust, solidarity and mutual care seem to me one of the most

important challenges of our time. How could we, how could our world cure

without solidarity, care for and trust in each other and without trust in a

truth beyond of what we can perceive and intellectually comprehend? Trust in

the divine along with solidarity and community with the indigent and the ostracized

were crucial points in Jesus' message and practice. After Jesus' death his

followers did not seek – like the zealots – salvation in futile and suicidal

rebellion against Rome, but strived for inner liberation by the means of

meditation, love and reconciliation. Are those principles applicable to the

problems of today? I think yes.

Christ

In

the Christian tradition of faith Jesus is called "Christ". The Greek

word "Christós" means "the anointed", in Hebrew "Meschiach".

Chilton explains that the

term “Messiah” could be defined in different ways in ancient Judaism. Messiah

could refer to one chosen of God from the house of David to rule as king and to

achieve the expected removal of foreign dominion by war. Messiah could also

mean anointed to offer sacrifice, or anointed to prophesy. The Old

Testament's Book of (the second) Isaiah speaks about a servant of God assigned to

call Israel to its vocation as the people of God and to lead the other nations, but

also to endure horrible suffering:

"He was despised,

and forsaken of men, a man of pains, and acquainted with disease, and as one

from whom men hide their face: he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely

our diseases he did bear, and our pains he carried; whereas we did esteem him

stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded because of our

transgressions, he was crushed because of our iniquities: the chastisement of

our welfare was upon him, and with his stripes we were healed. All we like

sheep did go astray, we turned everyone to his own way; and the Lord hath made

to light on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed, though he humbled

himself and opened not his mouth; as a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and

as a sheep that before her shearers is dumb; yea, he opened not his mouth. (…) He

had done no violence, neither was any deceit in his mouth. Yet it pleased the

Lord to crush him by disease; to see if his soul would offer itself in restitution,

that he might see his seed, prolong his days, and that the purpose of the Lord

might prosper by his hand: Of the travail of his soul he shall see to the full,

even My servant, who by his knowledge did justify the Righteous One to the

many, and their iniquities he did bear. Therefore will I divide him a portion

among the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the mighty; because he

bared his soul unto death, and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore

the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors." (Isaiah, Chapter 53)

Many

Christians believe that this text heralds the messianic role and passion of

Jesus. Chilton does

not share the view that Jesus saw his role in intentional suffering and in

sacrificing himself. Jesus' own idea of his messianic role was

rather to be chosen of

God and empowered by the holy Spirit for his particular prophesy. There is no

evidence that Jesus considered himself as a divine figure, as the only son of

God or as the lamb of God designated to die for the salvation and redemption of

Israel. Such an exalted meaning of the Messiah

appeared only later.

There is broad consensus among

scholars that the Gospels cannot be considered as literal history. After

280 years of scientific quest for the historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer's

claim remains still valid that a solid and precise historical reconstruction of

Jesus' life is impossible. But are the Gospel just fanciful Hellenistic fairy tales and useless for

historians? Did the evangelists and later Christian authors even

deliberately manipulated and fraudulently altered the original facts? Chilton

would not agree with such a stance although he holds that the authors of the

Gospels extensively reworked, arranged and edited the available accounts of

Jesus and his ministry.

Everybody

who had encountered Jesus had made his or her utterly subjective experience

with him. Therefore the accounts of Jesus rendered by different individuals

varied of course. The stories and the pictures of Jesus, as they are conveyed

in the Gospels and in the later Christian literature, consist of hundreds,

maybe thousands of individual encounters, emotional reactions, intellectual

preoccupations, spontaneous imaginations, intuitions and interacting

narratives. Thus the Gospels might reveal much more about the needs, longings,

projections, cultural backgrounds and states of consciousness of those whose

experiences and accounts are melted together in the New Testament than about

the real person of Jesus.

If

we do not view Jesus as an unique figure, chosen by God to play the dominant

role in a particular divine plan, but if we look on Jesus as just the prominent

opponent of a collective development process evolving a novel kind of

spirituality and religious practice within ancient Judaism, we must not lament

the persistent vagueness of Jesus' historical profile. Instead we can focus on

the obvious outcome of that process, what was in fact the notion of Jesus as a

divine figure. Obviously there was and there still is a strong need to exalt

Jesus and to exalt oneself by participating in Jesus' messianic glory. According to Chilton Jesus

himself rejected the role of a victorious messiah. He resisted the temptation

of being exalted and insisted that his followers learn the same humility. He

taught them to recognize that one is limited, weak, in need of nurture and

forgiveness in the presence of the creator of all things.

I would like to close my provisional

review by posing some questions: What is the particular Christ quality that

Jesus could have had in mind? What kind of Christ quality is appropriate nowadays?

How can that Christ quality contribute to individual and collective healing, to

liberation from fear, hate and despair, to more solidarity and mutual care, to

preventing the world from further war, terror and ecological suicide?

Ich verstehe es genau anders herum. Es ist nicht der Weg, Jesus zurück auf eine rein menschliche historische und psychologische Ebene zu reduzieren.

AntwortenLöschenNatürlich hat er als Mensch (-ensohn) diese Anteile ganz unbestritten in sich getragen.

Aber der mystisch geistige Teil seiner Individualität wird ja von allen Weisheitskulturen der Menschheit in sehr ähnlichen Worten bestätigt. Nicht umsonst tauchen solche Thesen, seiner Verbindung zum Bhudismus, immer mal wieder auf. Das ist aber ganz unnötig.

Seine Abgrenzung (als Prophet oder mehr) gegenüber Schriftgelehrten und Priestern ist ja nicht um sie herauszufordern erfolgt. Sie grenzte vielmehr seine Worte in "Vollmacht" eindeutig von den religiösen "Schriften" und Behauptungen ab, die verändert und missbraucht als Machtinstrumente der Priester aller Zeiten fungieren.

Spätestens, seit die unvoreingenommenen und wirklich wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen des Grabtuches von Turin eine (nahezu) unzweifelhafte Zuordnung zu Jesus ermöglichen, brauchen wir weder an dem Kern der Evangelien noch ernsthaft zu zweifeln, noch an der Auferstehung als physikalisch sowie geistig. Physik (Materielles) und Geist zu trennen macht einfach keinen Sinn mehr.

Wenn man versucht die mystische Bedeutung Jesu von seinem Menschsein zu trennen, wird man etwas ähnliches bemerken wie wenn man Psychologie ohne den Anteil des Wunderbaren, Heiligen und Geistigen betreiben und verstehen möchte.

Warum funktionierte z.B das Communitybuilding von Morgan Scott Peck mit ihm selbst so wunderbar?

Warum verflacht es in den Gruppen, die es heute noch ausbilden oder "anwenden" (zumindest meiner Erfahrung nach) zu einem Verweilen in Fühlen? Warum suchen die Leute in allerlei Alternativen (oft viel komplizierter und mit viel Drumherum) einen anderen Weg?

Ich denke es ist weil man überall nicht "das Höhere, das Transzendente" dabeihaben möchte sondern lediglich von Feldern und Energien reden und damit handeln möchte.

Jesus ist von "dem Vater" (Vater und Mater) ebensowenig zu trennen wie WIR ALLE und auch der Prozess zum WIR erst funktioniert, wenn wie Peck es selber ausdrückte "wir Gott ins Boot lassen und es sich dann viel leichter rudert"

Zurück zum Anfang: Nicht Jesus "zu uns in das Menschliche herunterholen” sondern, uns als ebenso göttliche Potenzialitäten erkennen wie Jesus es ganz offenbar vorgelebt hat und aussprach.

"Ich bin der Weg, die Wahrheit und das Leben"! ... "Wisst ihr nicht, das gesagt wurde, ihr seid Götter?"

Auch das Communitybuilding von M. Scott Peck weist diese Signaturen auf: Weg, Wahrheit, Leben und nach dem Chaos und dem Gang durch die Leere wird ein jeder in seine individuelle Kraft geleitet.